Abstract

This chapter examines how well migrants integrate in the Swiss labour market. In the year of arrival in Switzerland, the employment rate and labour income of migrants are below those of people-born in Switzerland. Over the course of their stay, however, migrants can significantly reduce this gap. The employment rate of migrant men after five years in Switzerland is only 4 percentage points below the level of men born in Switzerland, and the income of migrants is even slightly higher. Meanwhile, the employment rate of migrant women after five years is still 13% below the level of women born in Switzerland. Employed migrant women earn significantly more than women born in Switzerland as they work more hours on average. However, just over half of migrants leave Switzerland after a stay of less than five years.

3.1 Introduction

Since the turn of the millennium, Switzerland has significantly opened up its labour market internationally and the country’s economic attractiveness has subsequently led to high levels of immigration. This trend has sparked a broad political debate.

A key question in this debate is how well migrants integrate in Switzerland—particularly in the labour market.

This chapter will only address labour market integration. Other integration measures are not covered in the analysis.

Two questions are of interest, and will be further explored in this chapter:

– Are migrants able to gain a foothold in the labour market in the longer term or are they more likely than people born in

Switzerland to be unemployed or not employed for other reasons?

– Can employed migrants achieve a similar labour income to comparable individuals born in Switzerland?

Thanks to linked register data, we can analyse the employment careers of migrants over the course of their stay in Switzerland. We compare the achieved labour market outcomes with those of people born in Switzerland (not necessarily Swiss citizens), factoring in the different composition of the two groups in terms of sex, age, education and region of residence using regression analyses.

One area that is less studied but no less relevant is the increase not only in immigration but also in return migration brought about by the opening-up of the Swiss labour market. This opening-up therefore triggered dynamic social change. How well migrants integrate in the labour market is not the only crucial question, but also which migrants remain in Switzerland in the longer term. This chapter therefore also highlights to what extent return migration is linked to the labour market.

In terms of methodology, we adhere to a study that we authored for the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) in 2018 (Favre, Föllmi, and Zweimüller 2018). Thanks to new data, we are able to update the analyses and examine individual aspects in more detail.

There are also content-related links to Chapter 2 in this publication. In Chapter 2, one of the things that Philippe Wanner looks at is also the gap in labour income between migrants and people born in Switzerland. The difference in this chapter compared with the income comparison is that Wanner does not track a particular group of persons over time, rather he considers the whole cohort at any given time. In addition, the influence of age, education and region of residence on earnings is not stripped out from the income gap between migrants and people born in Switzerland. Chapter 2 therefore reveals the income gap between people born in Switzerland and all migrants in a cohort every year since the migrants in the cohort arrived in Switzerland, while this chapter shows how individual migrants integrate in the labour market in relation to comparable people born in Switzerland.

Box 3.1: Research data

For the analyses, individual data sets from the following sources were linked up:

Individual OASI accounts (IA) (Central Compensation Office CCO): employment status and earnings of all persons from 1981 to 2016;

Population and Households Statistics STATPOP (Federal Statistical Office FSO): age, sex and place of residence of all persons from 2010 to 2017, as well as household composition;

Structural survey (FSO): qualifications (education, learned occupation) and working time in the period 2010 to 2017 for approx. 300 000 randomly selected persons in the permanent resident population;

Central Migration Information System ZEMIS (State Secretariat for Migration SEM): date of immigration and emigration, residence status and place of residence of foreign nationals from 2003 to 2017.

The population of the data set is made up of Swiss nationals who were resident in Switzerland for at least one year between 2010 and 2017, and foreign nationals who were resident in Switzerland at the beginning of 2003 or who have moved to Switzerland since. Persons who immigrate to Switzerland as asylum seekers are only considered once they are issued a residence permit.

3.1.1 Methods and definitions

Methods

Our analyses take into account persons aged between 25 and 65 (descriptive analyses) and persons aged between 25 and 55 (regression analyses). There are two reasons for restricting the analyses to these age groups. First, persons aged under 25 and over 55 are under-represented among migrants, which limits comparability with people born in Switzerland. Second, those under 25 are often still in education and therefore earn below-average incomes.

To analyse integration, we compare the labour market outcomes of migrants throughout their stay in Switzerland (study group) with the labour market outcomes in the same period of people born in Switzerland (control group). See Table T1.1 in Chapter 1. Here in Chapter 3, people born in Switzerland are compared with migrants, i.e. with people born abroad who did not have Swiss citizenship when they arrived in Switzerland. As we are interested in individual integration trajectories, we only include people who lived in Switzerland throughout the entire study period in the analysis of employment and unemployment (in the case of our main results: five years). For the analyses of labour income we similarly considered persons who earned an income from employment throughout the entire study period. If we also included persons in the analyses who left Switzerland or gave up their employment before the end of the study period, the measured differences between the study and control group would no longer only reflect the integration trajectory, but also the changing composition of the study group.

To improve the comparability of the study and control groups, we exclude people aged under 25 and over 55, and conduct the analyses separately for men and women. In our regression analyses, we also consider subjects’ age, qualifications and region of residence. So, in effect, we compare migrants with comparable individuals—measured using these characteristics—who were born in Switzerland.

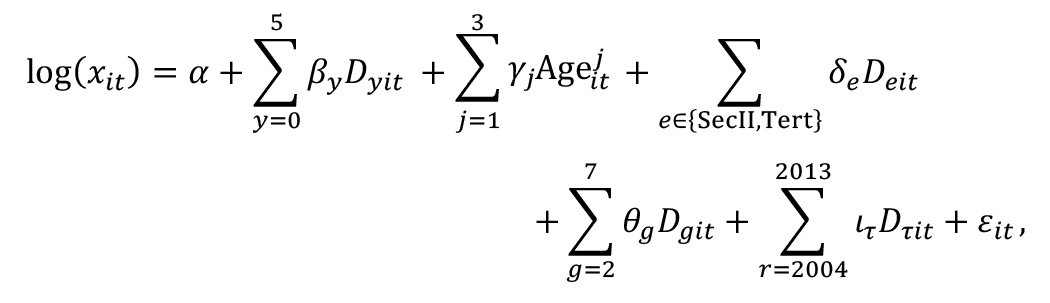

For this purpose, we estimate regression equations of the type

denotes the labour market outcome studied (labour income, employment rate, unemployment rate) of person

denotes the labour market outcome studied (labour income, employment rate, unemployment rate) of person  in calendar year

in calendar year  ;

;  an indicator variable that assumes the value 1 if person

an indicator variable that assumes the value 1 if person  in year

in year  has been in Switzerland for years

has been in Switzerland for years  and 0 if they belong to the control group;

and 0 if they belong to the control group;  the age of person

the age of person  in year

in year  ;

;  ,

,  indicator variables that take value 1 if person

indicator variables that take value 1 if person  in year

in year  has an upper secondary or tertiary level qualification;

has an upper secondary or tertiary level qualification;  an indicator variable that assumes value 1 if person

an indicator variable that assumes value 1 if person  in year

in year  lives in region

lives in region  ;

;  an indicator variable that assumes value 1 if

an indicator variable that assumes value 1 if  (calendar year effects).

(calendar year effects).

We are interested in the coefficients  . These measure the differences in terms of labour income, employment rate and unemployment rate between people born in Switzerland and comparable migrants in the twelve months after they arrive. A comparison of these coefficients therefore shows the average integration trajectory.

. These measure the differences in terms of labour income, employment rate and unemployment rate between people born in Switzerland and comparable migrants in the twelve months after they arrive. A comparison of these coefficients therefore shows the average integration trajectory.

As the migrant group is extremely heterogeneous, we differentiate our results in various dimensions. So, for example, we present the results by country of origin separately, as migrants from EU and EFTA states find it easier to integrate than migrants from third countries due to comparable education systems and labour market structures and the fact that migrants from neighbouring countries already speak one of Switzerland’s national languages. There are also major differences in qualification level between migrants. Compared with those born in Switzerland, people with a low level of education (lower secondary or less) and those with a high level of education (tertiary level) are over-represented among migrants (see also Chapter 1.4.2). Within these groups, however, there are a disproportionately high number of migrants with particularly low and particularly high incomes.

We therefore also calculate regressions separately by region of origin, to compare the integration trajectory of those from EU and EFTA states with that of people from third countries, for example. In addition, we also present the coefficients separately by education group to highlight whether the average figures conceal differences in qualifications between migrants. This is of particular importance in the analysis of income trajectories as here the average values may be heavily driven by high incomes. We therefore analyse in a separate section how the distribution of migrants’ earnings and those of people born in Switzerland evolve more or less in tandem over time.

For all these analyses the study period is the first five years after the year of arrival. All those who left Switzerland within this period are thus excluded from the analyses on employment and unemployment, and those who were not continuously employed are excluded from the income analyses. An analysis of residence histories shows that half of migrants leave Switzerland within the first three years. We therefore document the integration trajectories of people who stayed between one and thirteen years. This provides us with a complete and differentiated picture of how well migrants integrate in the labour market both in the short and longer term.

In addition, we look at which factors influence the length of stay. In particular, we highlight the link between labour market success and probability of return migration. We thus analyse whether people who have trouble finding employment or who lose their job are likely to remain in Switzerland or return to their country of origin. We also show whether people with above average income or a particularly steep income profile stay longer in Switzerland due to their success on the labour market, or whether such individuals are particularly internationally mobile and therefore soon leave Switzerland.

Definitions

In our analyses we compare the labour market outcomes of migrants with those of people born in Switzerland. See Table T1.1 in Chapter 1. The migrant group comprises foreign nationals who immigrated to Switzerland within the study period and who were between 25 and 55 years old during the entire study period. These individuals remain in the migrant group, even if they are subsequently naturalised. The control group is made up of people aged between 25 and 55 who were born in Switzerland, even if they are not Swiss nationals.

We measure the labour market integration of migrants in terms of the extent to which they participate in the labour market and the level of income they earn if they are employed:

– Our primary measurement for labour market participation is the employment rate. It is calculated by dividing the number of employed and self-employed people by the total number of persons in the relevant group. The complementary measurement to the employment rate is the proportion of not employed persons in the group. Not employed persons comprise unemployed and economically inactive people. In our study, people are deemed unemployed in the months in which they draw unemployment benefits. Economically inactive people are defined as those who are neither self-employed or employed nor unemployed in a given month.

– Income comparisons are based on average monthly income from employment. As working hours and work-time percentage (for part-time work) are not recorded in the available data sources (see Box 3.1), we cannot calculate hourly wages or standardised income. In the case of men, hourly wages and monthly income are strongly correlated, as their average work-time percentage is very high. In the case of women, however, differences in income do not directly imply differences in hourly wages.

3.1.2 Literature

How well migrants integrate in the labour market of their host country has long been a core question of migration research. In early works, Chiswick (1978) and Borjas (1985, 1987) used cross sectional data to examine the correlation between length of stay and the income ratio of migrants and US nationals in the United States. Borjas (2015) updated these analyses. As these studies are not based on longitudinal data, however, but on (repeated) cross sections, they cannot show individual integration trajectories, but only the average evolution of a cohort of migrants. However, as the composition of such cohorts is constantly changing due to return migration, integration cannot be distinguished from the consequences of the changed composition.

Only in the last two decades has migration research analysed longitudinal data in order to highlight integration trajectories. Hu (2000) and Lubotsky (2007) examine individual differences in earnings between migrants and natives using US administrative data. They find that over time migrants are able to close the migrant-native earnings gap. Bratsberg et al. (2010, 2014) analyse Norwegian administrative data and in contrast to the previous authors not only consider income, but also employment. They found that migrants from European countries leave Norway after just a few years on average. Migrants from countries outside Europe stay longer in the country, are initially well integrated in the labour market but increasingly leave it after around ten years to claim social insurance benefits instead.

There is very little literature relating to Switzerland in this area. The first study based on administrative longitudinal data was conducted by Fluder et al. (2013) on behalf of the Control committee. It is based on linked social insurance and migration register data. The authors only use the longitudinal dimension of their data to calculate the length of stay, and then analyse the incidence of unemployment and social insurance claims in cross sections. Two other studies look at the labour market outcomes of foreign nationals in Switzerland. Steinhardt et al. (2013) compare native Swiss with naturalised Swiss citizens and foreign nationals. A study by BASS (2015) compares migrants from countries affected by the European debt crisis with migrants from other EU countries.

The authors of this chapter already analysed the integration of migrants in the labour market on behalf of SECO in 2018 (Favre, Föllmi, and Zweimüller 2018). Methodologically we draw on these existing studies, but we go further in several dimensions. First, a new data set allows us to extend the study period by three years, to 2016. This allows us to analyse integration over a longer period, and allows us to incorporate additional cohorts in the analyses. Furthermore, we highlight the significance of the household situation in labour market decisions and thus integration. To take better account of the heterogeneity of migrants, we expand the analyses of distribution of labour income. Finally, we document the integration trajectories of persons with different lengths of stay in Switzerland and analyse how labour market success influences return migration, in order to obtain a more complete picture of integration.

3.2 A comparison of the labour income

structure of migrants and people born

in Switzerland

The number of migrants arriving in Switzerland every year rose steadily between 2003 and 2013. Immigration has since fallen slightly, but in 2017 was still well above 2003 levels. The proportion of migrants from EU and EFTA states was consistently at around 80%.

By and large, these migrants have integrated well in the labour market, but they do not achieve quite the same labour market participation as people born in Switzerland on average. For example, at 78% for men and 66% for women, the percentage of employed migrants aged between 18 and 65 in 2015 was relatively high, but was still significantly below the labour force participation of the comparable population born in Switzerland (85% for men and 78% for women).

A descriptive analysis shows that employed migrants even earn a slightly higher average income than those born in Switzerland. This extremely positive integration picture must be viewed in a differentiated manner, however. On the one hand, the employment rate of migrants is lower. On the other, we need to distinguish between men and women as there are clear differences in work-time percentage. Both male migrants and men born in Switzerland are for the most part in full-time employment and in 2016 earned about the same average monthly income of CHF 7540. Meanwhile, employed migrant women work on average around 10% more than employed women born in Switzerland, and in 2016 also earned 10% more, with an average monthly income of CHF 4766. From this it follows that migrants and those born in Switzerland earn similar average salaries. However, these average values conceal considerable heterogeneity among migrants, as those with particularly high and those with particularly low incomes are over-represented compared with people born in Switzerland. This particularly applies to recent migrants.

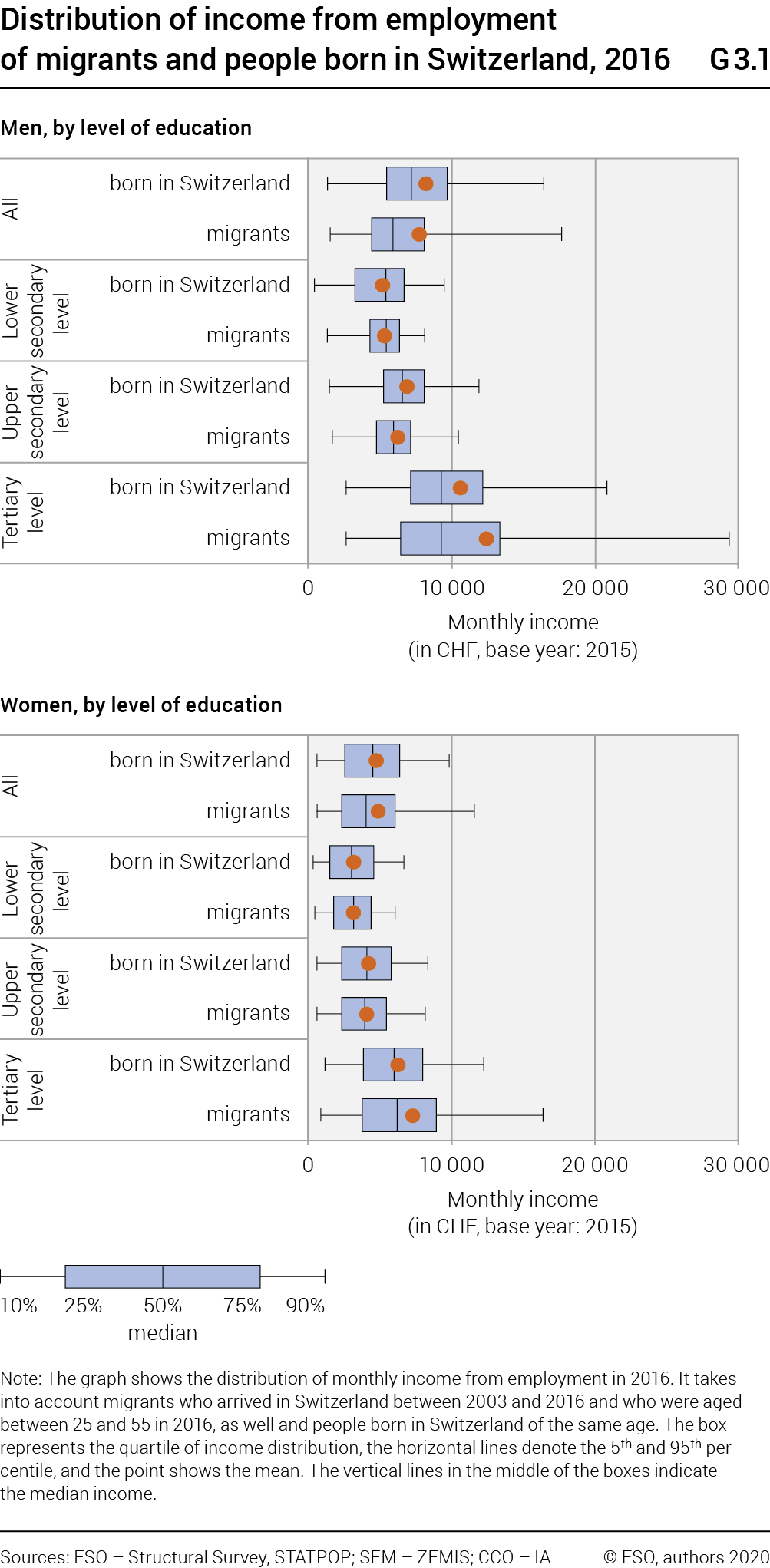

Graph G3.1 compares the income distribution of migrants and people born in Switzerland aged between 25 and 55. The box represents the quartile of distribution; the solid lines show the 5th and 95th percentiles and the point shows the average income.

Migrant and men born in Switzerland earn virtually the same average monthly income of around CHF 8000. Among migrants, however, there are slightly more individuals with low incomes and the 1st quartile is accordingly somewhat lower. This is offset by a larger proportion of individuals who earn a very high income. A comparison of education groups shows that there are many top earners among migrants who have completed tertiary education in particular, with 5% of this group earning more than CHF 30 000 a month.

Both among migrants and among people born in Switzerland, women earn lower monthly incomes than men. As a descriptive analysis of the Swiss labour force survey shows, this is due in particular to the fact that on average women are more likely to work part-time and thus fewer hours per week. Migrant women also earn higher average incomes than women born in Switzerland as they work more hours on average. As working hours and work-time percentages are not recorded in the available data sources, we are unable to directly examine what portion of the documented income differences can be attributed to pay gaps and what portion is due to differences in working hours. However, analyses of the Swiss Labour Force Survey (SLFS) show that on average, migrant women work more hours than women born in Switzerland. As with men, the income distribution of migrant women is also more widely spread than that of women born in Switzerland.

3.3 Employment and unemployment

In this section we look at labour market integration measured in terms of employment rate and unemployment rate. To this end we compare migrants and people born in Switzerland, factoring in differences in age, education and region of residence.

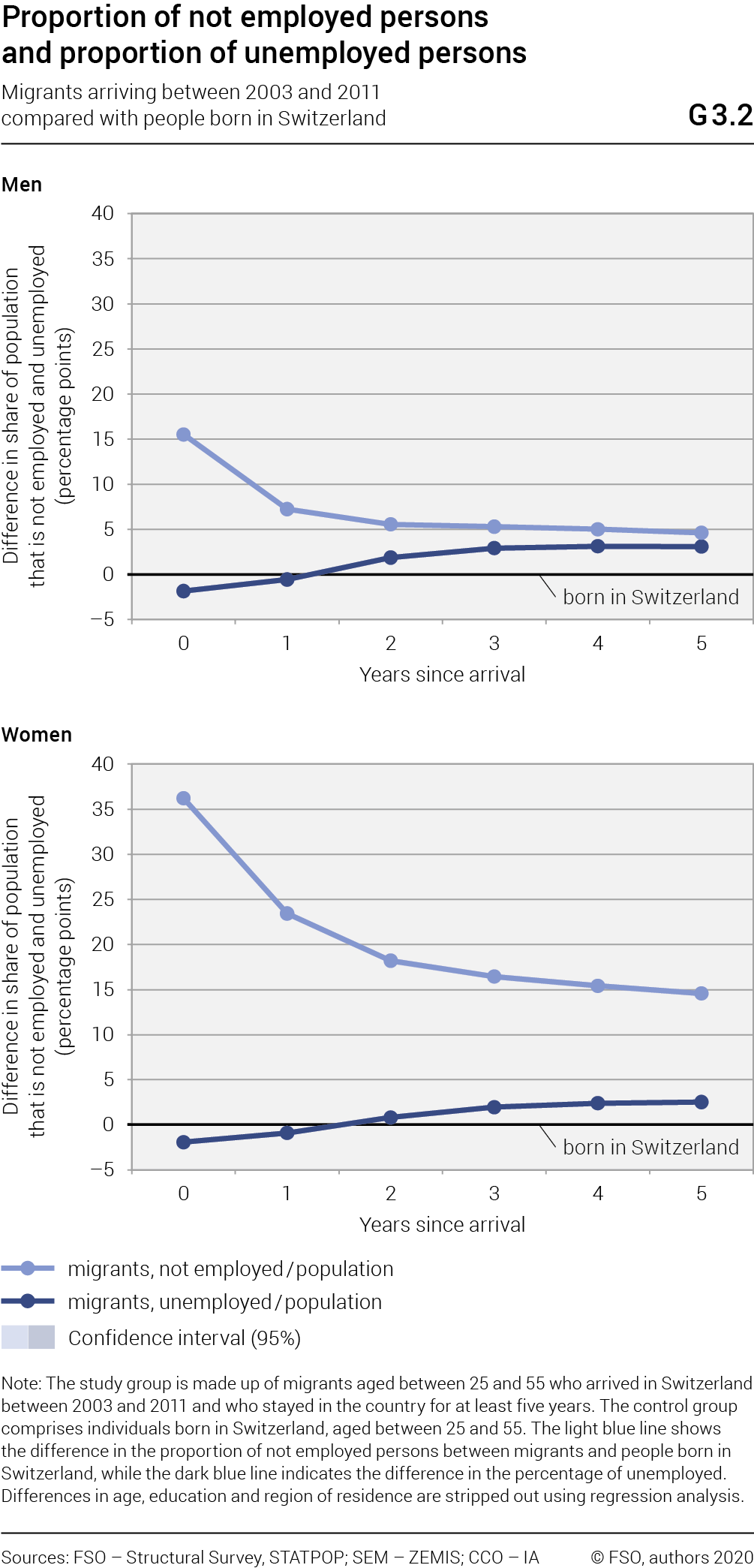

3.3.1 Differences in employment and unemployment over the course of a stay

Graph G3.2 shows the proportion of the population that is not employed and the proportion that claims unemployment benefit. The graph shows the differences between migrants and people born in Switzerland in each case, factoring in the differences owing to age, education and region of residence using the regression equation as set out in Section 3.1.1. The analyses include migrants who moved to Switzerland between 2003 and 2011, stayed for at least five years, and were aged between 25 and 55 during this time. The control group comprises persons born in Switzerland in the same age group who were resident in Switzerland during this time.

Among migrants, the proportion of not employed men in the year of arrival is 15 percentage points higher than that of men born in Switzerland. Over the course of their stay, however, this gap drops to just below 5 percentage points. Migrants are thus able to gain a good foothold in the labour market after a few years in Switzerland. The remaining difference can largely be explained by the higher risk of unemployment in migrants. While the unemployment rate among migrants is initially below that of people born in Switzerland, within five years it rises well above the rate of those born in Switzerland (see also Chapter 1.4.2).

The difference between migrants and people born in Switzerland is much greater in women. In the year of immigration, the proportion of employed migrant women is around 35 percentage points below that of comparable women born in Switzerland and even five years after immigration, there is still a discrepancy of around 15 percentage points. As opposed to men, only a small portion of this difference can be attributed to unemployment in women. Migrant women are thus much more likely than women born in Switzerland to remain completely outside the labour market, or they fail to find employment.

3.3.2 Differentiation by origin and education

Table T3.1 differentiates the above results by country of origin and education. For the sake of simplicity, the differences in employment rate—in other words the complementary value to no employment—are stated and the differences in unemployment are omitted.

Employment rate of migrants arriving between 2003 and 2011T3.1

Compared with people born in Switzerland (in percentage points)

| Years since arrival | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 years | 5 years | |

| Total | ||

| Men | –16.1 | –3.6 |

| Women | –37.3 | –13.3 |

| By country of origin | ||

| Men, EU/EFTA North-West | –9.2 | –3.3 |

| Men, EU/EFTA South | 2.3 | 3.0 |

| Men, EU/EFTA East | –13.1 | –2.7 |

| Men, third countries, recruitment countries | –29.8 | –8.8 |

| Men, third countries, other | –44.9 | –9.3 |

| Women, EU/EFTA North-West | –22.2 | –7.6 |

| Women, EU/EFTA South | –17.2 | 1.2 |

| Women, EU/EFTA East | –39.7 | –11.7 |

| Women, third countries, recruitment countries | –57.9 | –30.4 |

| Women, third countries, other | –60.3 | –25.4 |

| By education | ||

| Men, lower secondary level | –8.0 | 7.0 |

| Men, upper secondary level | –19.2 | –5.4 |

| Men, tertiary level | –17.0 | –6.7 |

| Women, lower secondary level | –30.6 | –3.5 |

| Women, upper secondary level | –37.6 | –13.0 |

| Women, tertiary level | –38.6 | –17.8 |

The study group is made up of migrants aged between 25 and 55 who arrived in Switzerland between 2003 and 2011 and who stayed in the country for at least five years. The control group comprises individuals born in Switzerland, aged between 25 and 55. The table shows the differences in the employment rates of migrants and people born in Switzerland. The second column indicates the difference in the year of immigration, and the third column the difference five years after immigration.

Sources: FSO — Structural Survey, STATPOP; SEM — ZEMIS; CCO — IA

© FSO, authors 2020

For the detailed analysis by country of origin, the countries are grouped according to a SECO categorisation. This categorisation draws a distinction between different EU and EFTA geographical regions, and between groups of third countries. The differentiation of third countries is guided by whether workers are primarily recruited from a country (e.g. India, United States, China, Japan), or not.

Among both men and women, migrants from EU and EFTA states integrate much better in the labour market than migrants from third countries. This is hardly surprising as these migrants are likely to find it easier to orient themselves in the labour market given the cultural proximity of their home countries to Switzerland. For example, many of them already speak one of Switzerland’s official languages on arrival. What is surprising is the low employment rate compared with people born in Switzerland of migrants from third countries from which workers are primarily recruited. Here, it is probably people who travel to Switzerland primarily for education and training purposes who remain outside the labour market.

If we differentiate the results by education group, it is striking that migrants with low qualifications fare better relative to those born in Switzerland than migrants with a high level of education. However, this is due to the fact that people born in Switzerland with a low level of education have a much lower employment rate than people born in Switzerland with a high level of education.

3.3.3 Employment and family situation

of migrant women

A comparison of male and female migrants shows that migrant men integrate more rapidly and more fully in the labour market than migrant women. Migrant women lag further behind women born in Switzerland from the very beginning and are less able to reduce this gap than migrant men.

A large proportion of these differences can be attributed to the family situation of migrant women, as shown in Table T3.2. After five years in Switzerland, unmarried migrant women aged between 30 and 55 achieve almost the same employment rate as women born in Switzerland of the same age (83% versus 86%). Of the married migrant women, on the other hand, only 61% are in gainful employment after five years in Switzerland. While the employment rate of married women born in Switzerland is also lower than that of unmarried women, it is still 80%. This suggests that the migration decisions of married women focus more on the husband’s professional situation than the wife’s employment opportunities.

Employment rate: a comparison of migrant women five years after arrival and women born in SwitzerlandT3.2

| Employment rate (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Migrant women after 5 years | Women born in Switzerland | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 61 | 80 | |

| Unmarried | 83 | 86 | |

| Household composition | |||

| Individual household | 87 | 87 | |

| Minimum 2 adults, no children | 77 | 86 | |

| Minimum 1 child aged 6 or above | 67 | 81 | |

| Minimum 1 child aged under 6 | 55 | 76 | |

The study group is made up of migrant women who were aged between 30 and 55 in the period 2012 to 2016 and had immigrated to Switzerland five years previously. The control group consists of women born in Switzerland of the same age. The table shows employment rates (in %) by marital status and household composition in the year under observation.

Sources: FSO — Structural Survey, STATPOP; SEM — ZEMIS; CCO — IA

© FSO, authors 2020

A similar picture emerges if we look at the composition of households in which migrant women and women born in Switzerland live. Migrant women who live in single-person households achieve the same employment rate as women born in Switzerland who live alone. Migrant women who live in a household with other adults (in many cases this is likely to be married women living in a household with their husband) are less likely to be in gainful employment than comparable women born in Switzerland (77% versus 86%). The difference is even greater between migrant women and women born in Switzerland in households with minor children. This indicates that migrant women are more likely to remain outside the Swiss labour market if they live with a partner who earns enough to support the family and if there are minor children in the household.

3.3.4 Differences between migrants with varying lengths of stay

The above analyses only include persons who stayed for at least five years in Switzerland. However, around half of all migrants left Switzerland after just three years. This raises the question as to whether the integration trajectories presented up to now convey an incomplete picture by excluding all those migrants who only stay in the country for a short period.

Furthermore, the previous analyses do not reveal anything about the longer-term integration of migrants in the Swiss labour market. Do migrants successfully gain a foothold in the labour market in the longer term, or does the discrepancy compared with people born in Switzerland increase again after a few years as migrants draw more social insurance benefits?

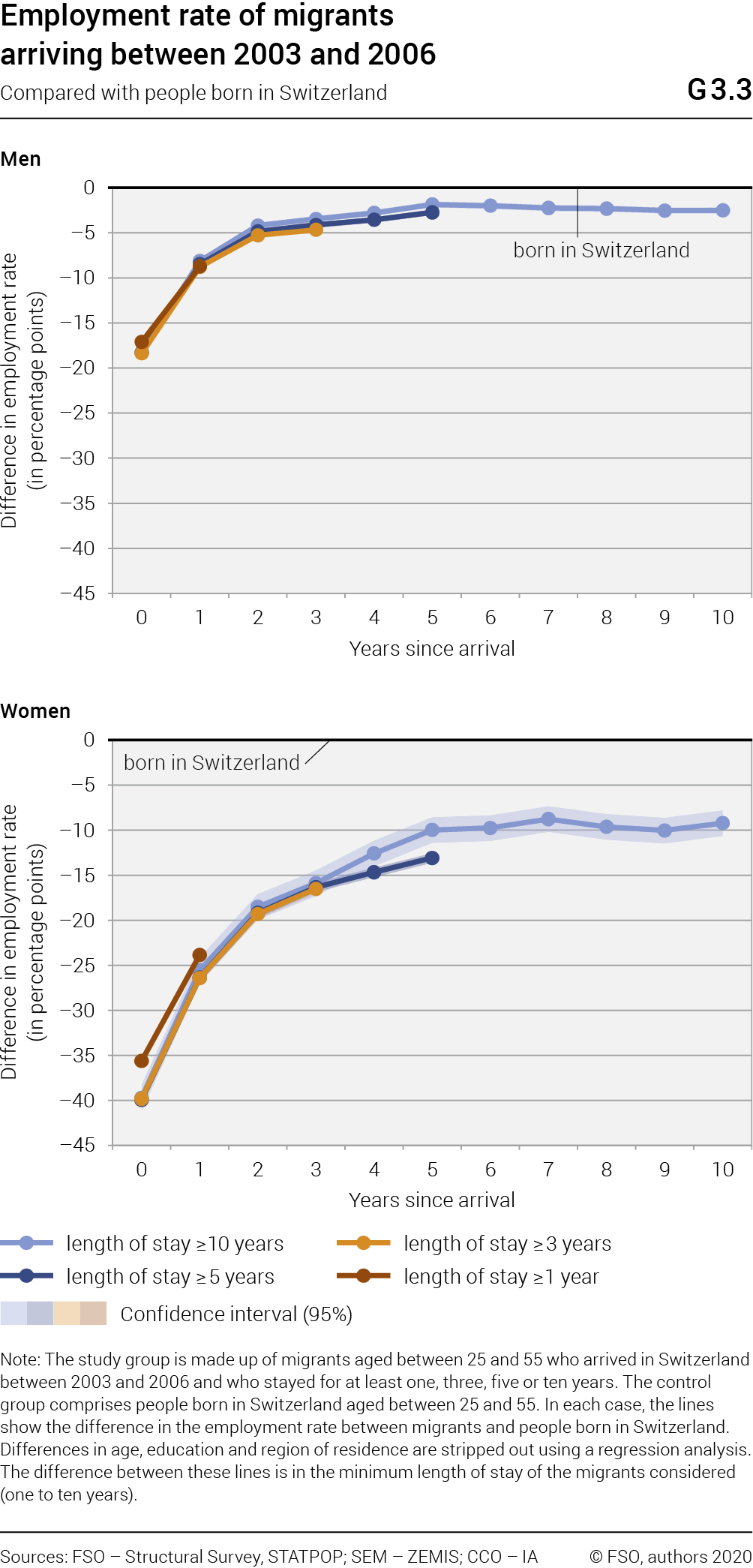

To answer these two questions, in this section we compare the integration trajectories of people who only stayed for a short time in Switzerland with the integration of persons who remained long term in Switzerland. To this end, we look at people who immigrated to Switzerland between 2003 and 2006 and who were aged between 25 and 55 during the study period. The control group is made up of people born in Switzerland of the same age.

The results of this analysis are shown in Graph G3.3. As in Graph G3.2, we factor in age, education and region of residence to make migrants and people born in Switzerland comparable. The red line shows the integration trajectory of migrants who stay in Switzerland for one year or longer. The other three lines shows the integration trajectories of migrants who stayed in Switzerland for at least three, five and ten years. In men, integration trajectories look similar, regardless of the length of stay. Migrant men initially exhibit a much lower employment rate, but in the first five years make up a large part of this discrepancy compared with men born in Switzerland. After around five years, the integration profile flattens out and a gap of around 3 percentage points remains. In women, too, the integration profiles look similar to Graph G3.2 irrespective of the length of stay, although the discrepancy between migrant women and women born in Switzerland further widens after the fifth year. After ten years, there is a discrepancy of just 9 percentage points.

If we only consider cohorts of migrants who arrived in 2003, we can track integration trajectories up to 13 years after arrival. There is no change compared with the finding above: the gap between migrant men and men born in Switzerland amounts to 2.4 percentage points after 13 years, while between migrant women and women born in Switzerland it totals 10.2 percentage points.

3.4 Differences in labour income

In this section we explore labour market integration measured in terms of monthly labour income. For this purpose, we compare migrants and people born in Switzerland, factoring in differences in age, education and region of residence.

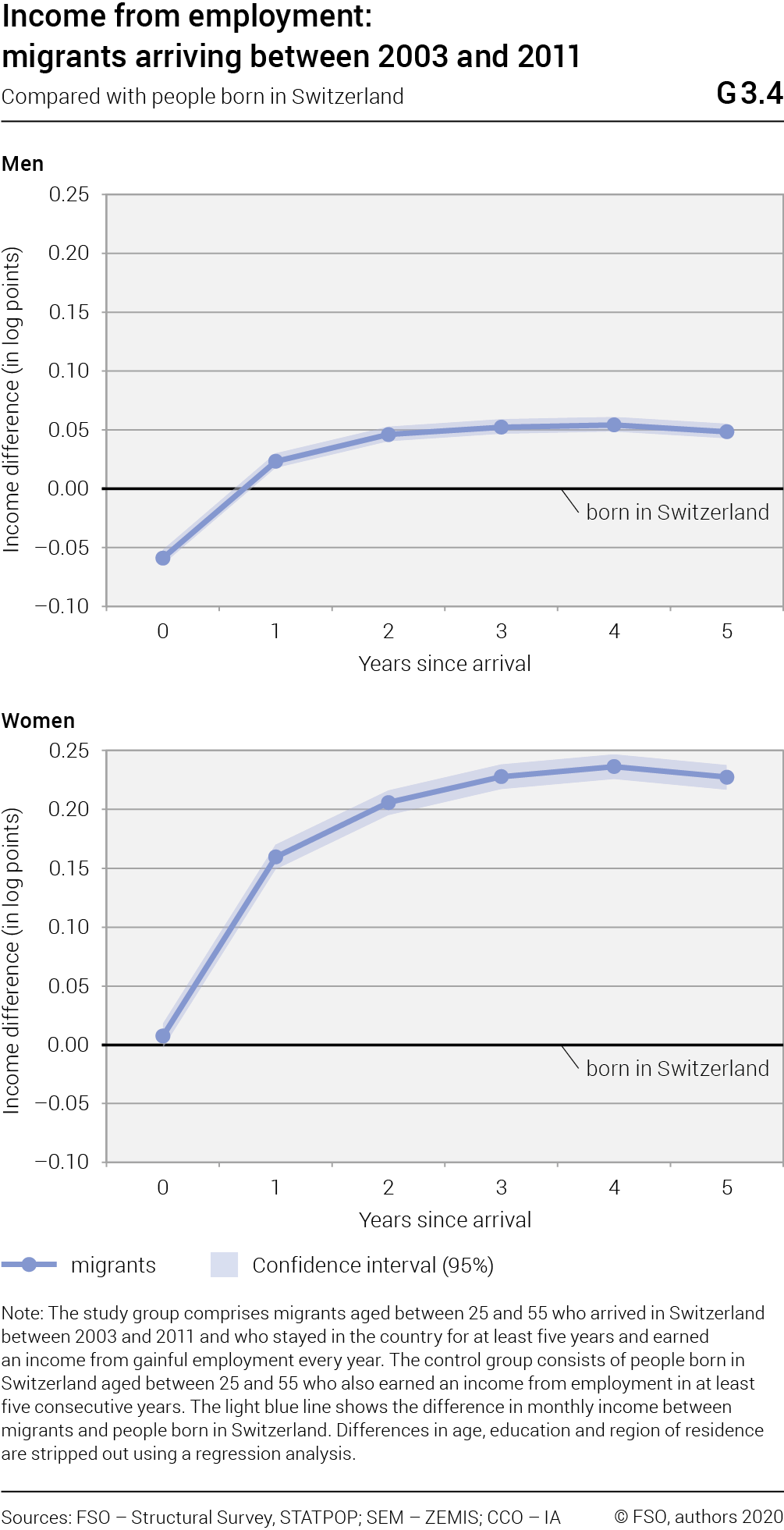

3.4.1 Income differences over the course of a stay

Graph G3.4 shows the difference in the average monthly income between migrants and people born in Switzerland. Again, the analysis includes male and female migrants aged between 25 and 55 who arrived in Switzerland between 2003 and 2011 and who stayed in the country for at least five years. The control group is made up of persons born in Switzerland aged between 25 and 55 who were resident in Switzerland during this period. For both groups, it is presumed that they earned an income from employment in each of the years being studied. The difference between the incomes is indicated in log points. A difference of 0.01 thus equates to an income difference of around 1%.

In the year of immigration, the income of migrant men is just over 5% below the income of men born in Switzerland, but they make up this difference within the first year of arrival. After five years in Switzerland, migrant men even earn more than comparable men born in Switzerland. Meanwhile, migrant women earn slightly more in the year of immigration than comparable women born in Switzerland, and this lead grows to over 20% within five years. A descriptive analysis shows that this is due to longer average working hours in migrant women, whereas average salaries of migrant women are at about the same level as those of women born in Switzerland (see also Section 3.2).

3.4.2 Income differences by education and nationality

Table T3.3 differentiates the above results by origin and education. It reveals that migrants from northern and western EU and EFTA states and those from the usual recruitment countries also fare particularly well in terms of earnings. Migrant men from these three groups and from southern EU and EFTA states integrate so well in the labour market that after five years they earn a higher income on average than men born in Switzerland. In migrants from eastern EU and EFTA states and—somewhat unsurprisingly—in migrants from third countries that do not belong to the usual recruitment countries, there is still an income gap even after five years. In women too, migrants from northern and western EU and EFTA states fare particularly well. However, after five years, all groups surveyed had integrated so well that they earned a higher income on average than women born in Switzerland.

If we analyse the education groups separately, it is striking that migrant men and women with an upper secondary qualification earn much lower incomes than comparable people born in Switzerland. This shows the high value the labour market attaches to the Swiss apprenticeship. In both men and women, the migrants who fare best are those who have a tertiary level qualification. Migrant men with a tertiary level qualification earn 14% higher incomes than comparable men born in Switzerland, while migrant women with a tertiary level qualification earn almost 30% higher incomes than women born in Switzerland.

Income from employment of migrants arriving between 2003 and 2011T3.3

Compared with people born in Switzerland (in log points)

| Years since arrival | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 years | 5 years | |

| Overall | ||

| Men | –0.058 | 0.049 |

| Women | 0.008 | 0.227 |

| By country of origin | ||

| Men, EU/EFTA North-West | –0.002 | 0.101 |

| Men, EU/EFTA South | –0.039 | 0.020 |

| Men, EU/EFTA East | –0.170 | –0.083 |

| Men, third countries, recruitment countries | 0.098 | 0.250 |

| Men, third countries, other | –0.264 | –0.056 |

| Women, EU/EFTA North-West | 0.175 | 0.350 |

| Women, EU/EFTA South | –0.145 | 0.134 |

| Women, EU/EFTA East | –0.121 | 0.134 |

| Women, third countries, recruitment countries | 0.148 | 0.373 |

| Women, third countries, other | –0.328 | 0.081 |

| By education | ||

| Men, lower secondary level | –0.111 | 0.060 |

| Men, upper secondary level | –0.266 | –0.122 |

| Men, tertiary level | 0.068 | 0.138 |

| Women, lower secondary level | –0.200 | 0.126 |

| Women, upper secondary level | –0.048 | 0.164 |

| Women, tertiary level | 0.164 | 0.279 |

The study group comprises migrants aged between 25 and 55 who arrived in Switzerland between 2003 and 2011 and who stayed in the country for at least five years and earned an income from gainful employment every year. The control group consists of people born in Switzerland aged between 25 and 55 who also earned an income from employment in at least five consecutive years. The table shows the differences in average monthly income between migrants and people born in Switzerland. The second column indicates the difference in the year of immigration, and the third column the difference five years after immigration.

Sources: FSO — Structural Survey, STATPOP; SEM — ZEMIS; CCO — IA

© FSO, authors 2020

3.4.3 Income differences along the income distribution

As shown in the previous section, the average incomes of migrants conceal significant income differences. The positive integration shown in Graph G3.4 could thus be driven by a particularly positive development among top earners. Indeed, the separate analysis by education group in Table T3.3 shows that highly-qualified migrants have a particularly steep income trajectory relative to the control group of people born in Switzerland. However, this analysis also shows that low-qualified migrants also integrate rapidly in the labour market and earn comparable incomes to low-qualified people born in Switzerland after five years.

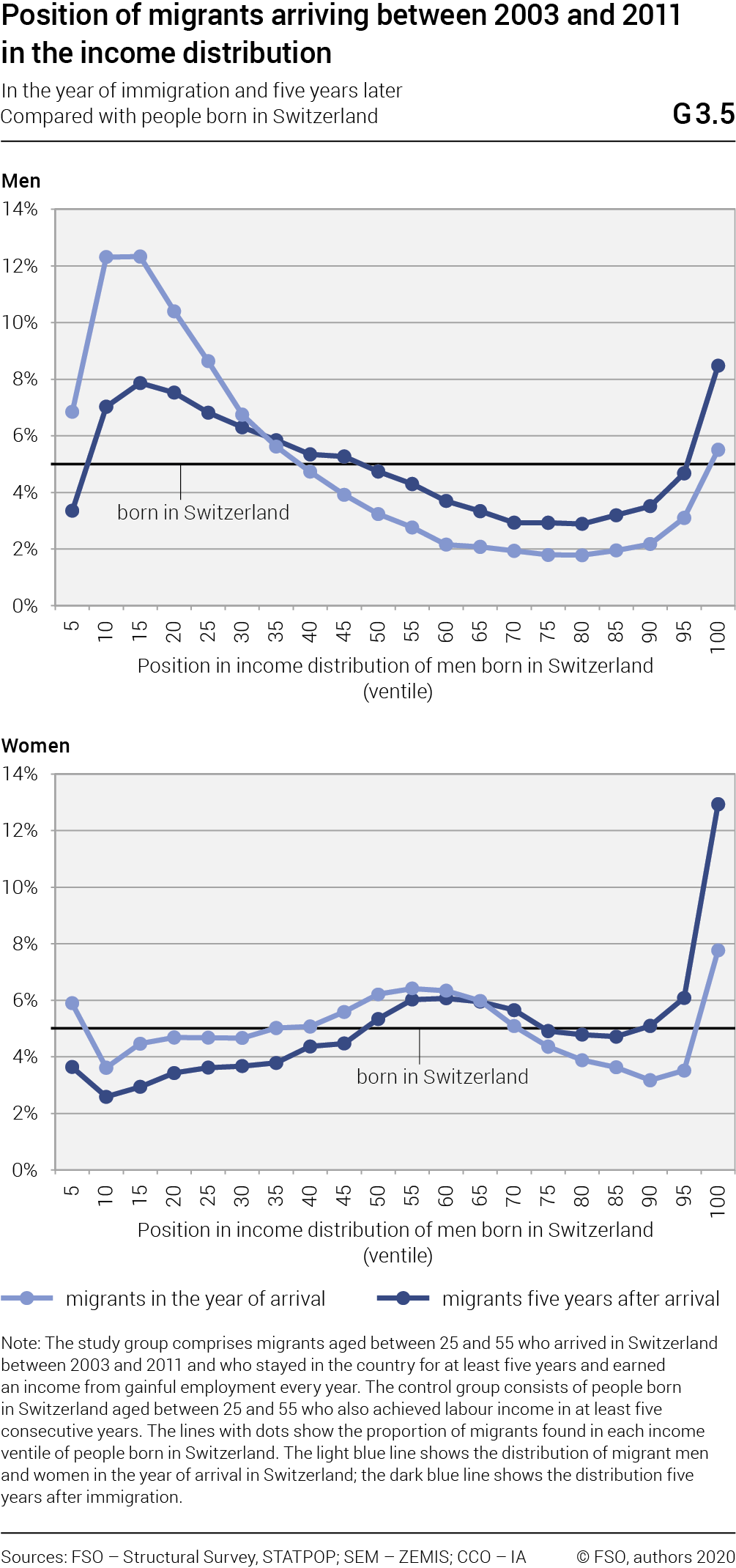

Graph G3.5 once again clearly shows this outcome. To draw up this graph, the income of people born in Switzerland was first compared with that of migrants, controlling for age, education and region of residence. We split the (controlled) income of both groups into twenty groups of equal size (ventiles). The light blue lines show the proportion of migrants who fall into each of these ventiles in the year of immigration. If the income distributions of migrants and people born in Switzerland were identical, these lines would be horizontal at 5% (i.e. 5% of migrants would fall in every income ventile of people born in Switzerland).

Migrant men are significantly over-represented in the lowest income ventiles, under-represented in the middle of the income distribution and again slightly over-represented in the top ventile. Recent migrants are thus disproportionately likely to earn particularly high or particularly low incomes. A similar picture emerges for women, although the distribution of migrant women has shifted marginally upwards because they work slightly longer hours on average than comparable women born in Switzerland.

The dark blue lines show the distribution of the same migrants (male and female) five years after arriving in Switzerland. In both men and women, the proportion of migrants has fallen at the lower end of the income distribution and increased at the upper end. This underscores that it is not only the top-earning migrants who achieve above-average income growth, but that the income distribution of migrants is approaching that of people born in Switzerland.

3.4.4 Differences between migrants with varying lengths of stay

The previous income analyses were limited to male and female migrants who stayed in Switzerland for at least five years. As outlined in the section on labour market participation, in this section we extend the focus to persons who stayed between just one year to ten years.

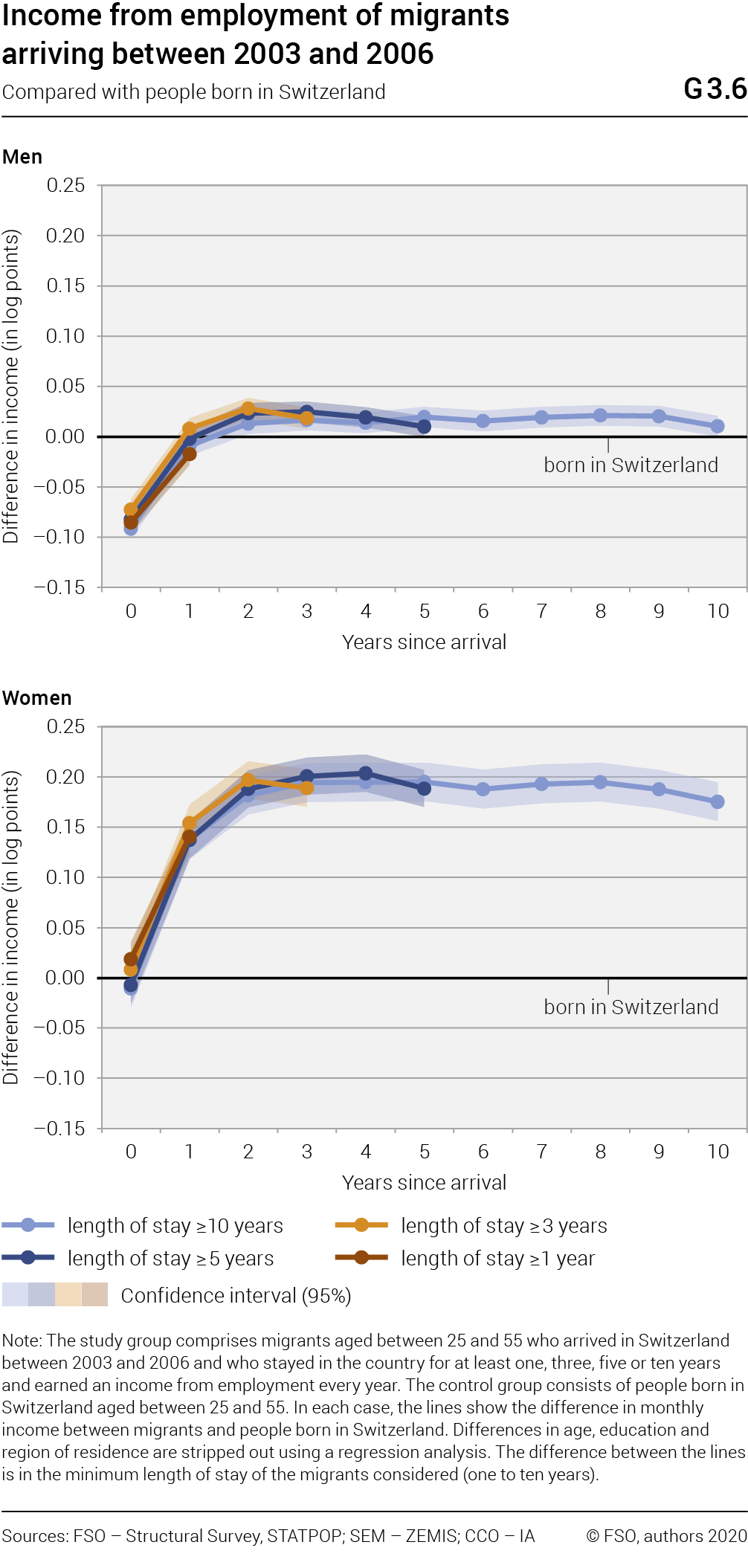

Graph G3.6 shows the income integration of people who immigrated to Switzerland between 2003 and 2006 and who were aged between 25 and 55 during the study period. The control group comprises people born in Switzerland who were in the same age group during this period. As in all previous analyses, we consider age, education and region of residence. The red line shows the integration trajectory of migrants who stayed in Switzerland for at least a year, while the other three lines show the integration paths of migrants who stayed at least three, five or ten years in the country.

Regarding income convergence between migrants and people born in Switzerland, there are no significant differences between those who had a short stay in Switzerland and those who remained for the longer term. In all cases, migrant men initially achieved significantly lower incomes than men born in Switzerland, instead enjoying much greater income growth in subsequent years. In the year of immigration, migrant women earn about the same as women born in Switzerland irrespective of their length of stay and also enjoy an above-average increase in income in the early years of their stay.

3.5 Return migration

In the first sections of this chapter, we looked at how male and female migrants integrate in the Swiss labour market during their stay in the country. It is in the nature of such analyses that they focus on migrants who stay for at least a short time in the country. But how many migrants stay for a short or longer period in Switzerland? And how does the length of stay in Switzerland relate to labour market success? We will now address these questions.

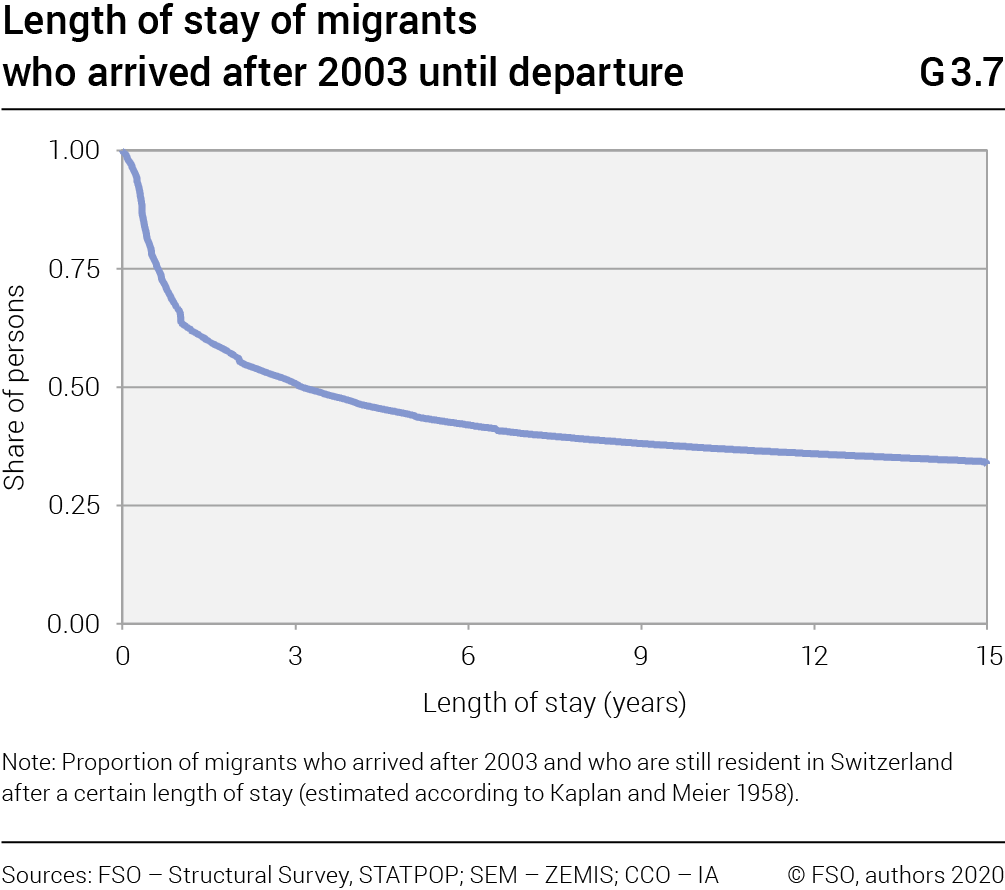

Graph G3.7 shows the proportion of the migrants who arrived in Switzerland after 2003 who are still in the country after a certain time. Here, we use the Kaplan and Meier estimator (1958). Indeed, many migrants only stay for a very short period in Switzerland: one third leave within the first year and just half of a migrant cohort stays in the country for longer than three years. After three years, the propensity to leave falls significantly, however (see also Chapter 2.5). Quantitatively and therefore macroeconomically, migrants who only stay for a very short time in Switzerland play a less important role than this graph would suggest—precisely because they only remain in Switzerland for a short time. If we take all migrants as a basis, more than half have already lived in Switzerland for over ten years, while the proportion of people who stay less than two years is only around a fifth.

Among those migrants who only stay in Switzerland for a year, many participate in the labour market from the outset. In both men and women, the employment rate of those who quickly leave Switzerland is above that of people who remain in the country for more than a year. However, in subsequent years a disproportionately high number of people who do not earn an income from gainful employment leave Switzerland, in other words those who do not work and are not unemployed.

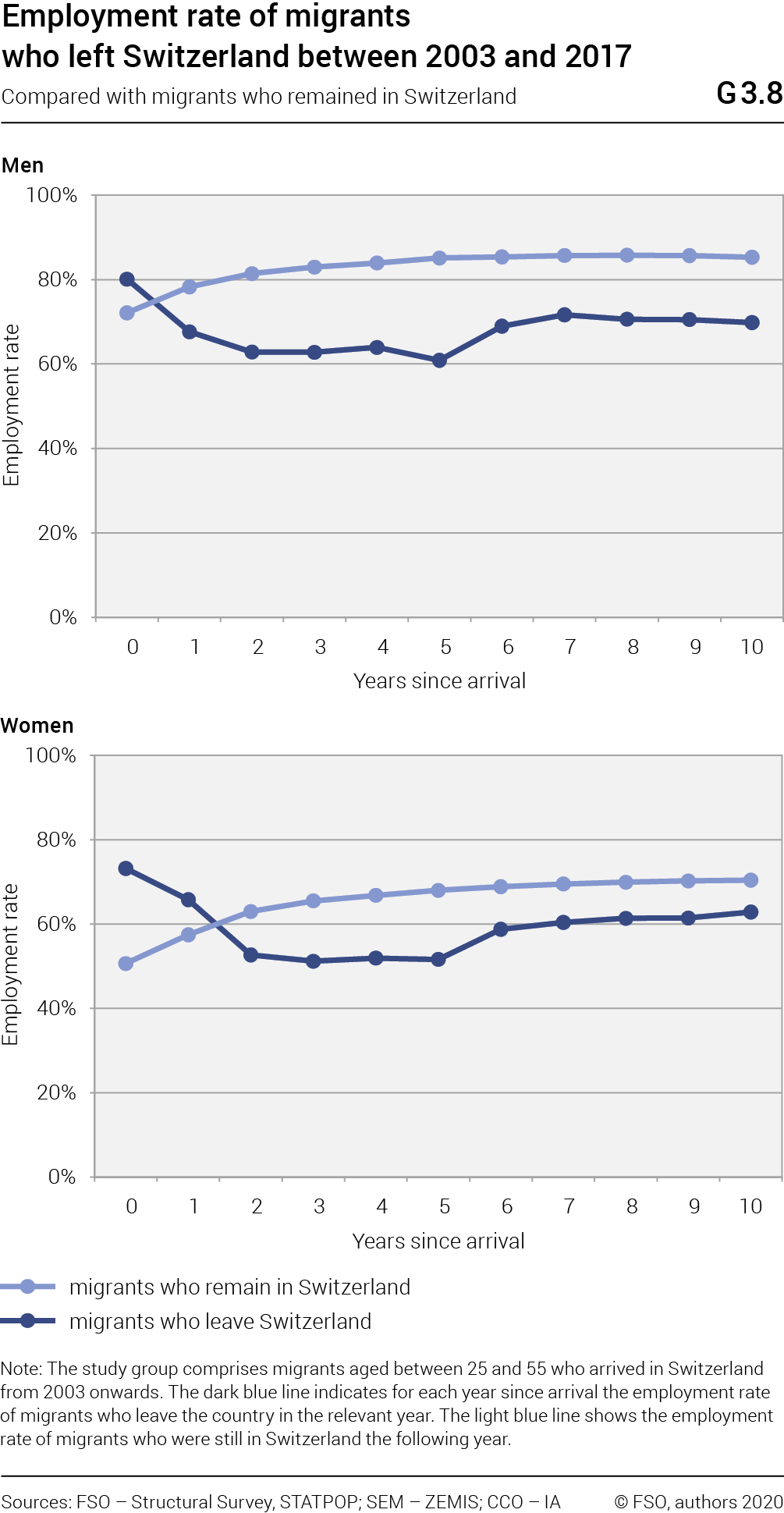

This correlation can be seen in Graph G3.8. The dark blue line shows the employment rate of people who leave Switzerland in the relevant year, while the light blue line shows the employment rate of those who remain in Switzerland. This includes people who arrived in Switzerland from 2003 and who are aged between 25 and 55.

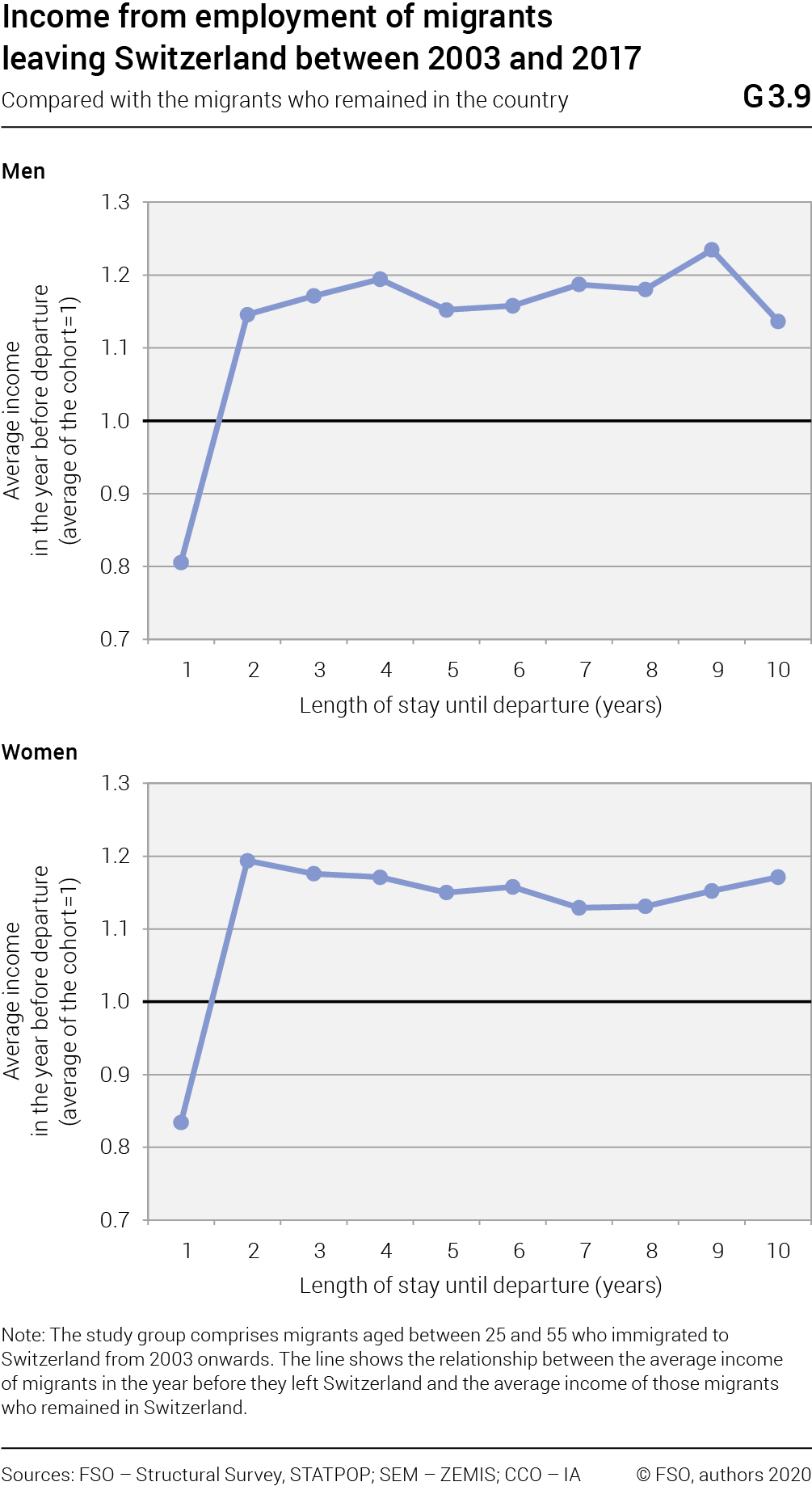

Graph G3.9 illustrates a similar analysis of labour income of emigrants and those who stayed in Switzerland. The line with dots compares the income of migrants the year they left Switzerland with the average income of the whole cohort in that year.

In the first year, it is primarily those with very low earnings who leave Switzerland. Those with a very short length of stay are thus frequently low-qualified workers who do participate in the labour market but who earn a below-average income. In the subsequent years, the average income of emigrants is around 10 to 20% above that of the migrants in the same cohort who remained in Switzerland. However, if we look at the income distribution of male and female emigrants, it is noticeable that people with both very high and very low incomes are over-represented. The high average income of emigrants is thus driven by some people with particularly high incomes. This therefore concerns highly-qualified workers who are active on an international labour market and are thus particularly mobile.

3.6 Conclusion

Our analyses show that migrant men are able to integrate rapidly and well in the Swiss labour market. While their employment rate in the year of arrival is around 16 percentage points below that of comparable men born in Switzerland, this gap narrows to just 4 percentage points after five years (see Table T3.1). In addition, employed migrant men rapidly make up the initial income gap and after five years even earn slightly higher monthly incomes than men born in Switzerland. However, they are more likely to be unemployed.

On the other hand, the employment rate of migrant women is significantly lower (– 37 percentage points) in the year of immigration than that of women born in Switzerland. Migrant women are also able to narrow this gap over the course of their stays, however, and after five years it amounts to just 13 percentage points. Employed migrant women also earn the same level of income in the year of immigration as women born in Switzerland, and 23% more after five years. This can be partly attributed to the fact that migrant women work more on average.

These average values conceal significant heterogeneity. If we compare the education structure of migrants with that of people born in Switzerland, we notice that among migrants, both those with a low level of education (lower secondary level or less) and those with a high level of education (tertiary) make up a larger proportion than among those born in Switzerland. This bimodal qualification structure is also reflected in income distribution, with male and female migrants over-represented at both the lower and upper ends of the income distribution. See also the study by Jey Aratnam (2012).

To make sure that our results are not driven by individual groups of migrants, we therefore differentiate our analyses by qualification and country of origin. The picture of positive integration is maintained in all sub-groups. There are significant differences in the extent of integration, however. In terms of employment rate, migrants with a low level of education fare better than migrants with a high level of education in relation to the Swiss control group. On the other hand, male and female migrants with a high level of education fare best in terms of labour income. In both dimensions, migrants from EU and EFTA states do better than migrants from third countries.

The analysis of income distribution for those who are employed also paints a very positive integration picture. While male and female migrants are still over-represented on the bottom end of the income distribution even after five years, this proportion significantly decreases over time. Conversely, the share of male and female migrants at the upper end of the income distribution increases. Male and female migrants are therefore able to catch up with the income distribution of people born in Switzerland across the board. Comparing income gains by quintile confirms this picture. All male and female migrants achieve positive income growth on average, and in all except the first quintile, this growth exceeds that of people born in Switzerland.

In our analyses we focus on migrants who stayed in Switzerland for at least five years. But we also extend this focus to take account of migrants who remained in Switzerland for less than five years. We note that the integration profiles of these people look very similar to the integration profiles of migrants who stayed in the country for longer. While they initially exhibit lower employment rates and average incomes, they are rapidly able to reduce the gap compared with people born in Switzerland. These extended analyses also show that even after ten years, the employment rate of migrants does not fall compared with that of people born in Switzerland. Migrants can therefore participate in the labour market in the longer term and do not slip into dependence on social insurance in significant numbers. However, among women in particular, a substantial gap remains compared with women born in Switzerland.

The migrants who remain in Switzerland thus integrate well in the labour market. Nevertheless, it is clear that many migrants leave Switzerland quickly, with over half leaving the country after less than three years. People with very low incomes have particularly short stays. In later years, more highly-qualified workers—who seem particularly internationally mobile—leave Switzerland, as well as people who were not employed in the country.

References

BASS (2015): Auswirkungen der Eurokrise auf die Zuwanderung aus der EU in die Schweiz. Schlussbericht im Auftrag des Staatssekretariats für Migration. Bern. https://www.buerobass.ch/kernbereiche/projekte/auswirkungen-der-eurokrise-auf-die-zuwanderung-aus-der-eu-in-die-schweiz/project-view (last accessed on 15.05.2020).

Borjas, George J. (1985): Assimilation, Changes in Cohort Quality, and the Earnings of Immigrants, Journal of Labor Economics, 3 (4), 463–489.

Borjas, George J. (1987): Self-Selection and the Earnings of Immigrants, American Economic Review, 77 (4), 531–553.

Borjas, George J. (2015): The Slowdown in the Economic Assimilation of Immigrants: Aging and Cohort Effects Revisited Again, Journal of Human Capital, 9 (4), 483–517.

Bratsberg, Bernt, Oddbjørn Raaum, and Knut Røed (2010): When Minority Labor Migrants Meet the Welfare State, Journal of Labor Economics, 28 (3), 633–676.

Bratsberg, Bernt, Oddbjørn Raaum, and Knut Røed (2014): Immigrants, Labor Market Performance and Social Insurance, Economic Journal, 124 (580), 644–683.

Chiswick, Barry (1978): The Effect of Americanization on the Earnings of Foreign-born Men, Journal of Political Economy, 86 (5), 897–921.

Favre, Sandro; Reto Föllmi, and Josef Zweimüller (2018): Der Arbeitsmarkterfolg von Immigrantinnen und Immigranten in der Schweiz: Einkommensentwicklung und Erwerbsbeteiligung im Längsschnitt. SECO Publikation; Arbeitsmarktpolitik No. 55 (10.2018). Bern: State Secretariat for Economic Affairs. https://www.seco.admin.ch/seco/de/home/Publikationen_Dienstleistungen/Publikationen_und_Formulare/Arbeit/Arbeitsmarkt/Informationen_Arbeitsmarktforschung/arbeitsmarkterfolg-immigranten.html (last accessed on 15.05.2020).

Fluder, Robert, Renate Salzgeber, Luzius von Gunten, Tobias Fritschi, Franziska Müller, Urs Germann, Roger Pfiffner, Herbert Ruckstuhl, and Kilian Koch (2013): Evaluation zum Aufenthalt von Ausländerinnen und Ausländern unter dem Personenfreizügigkeitsabkommen. Studie zuhanden der Geschäftsprüfungskommission des Nationalrats.

Hu, Wei-Yin (2000): Immigrant Earnings Assimilation: Estimates from Longitudinal Data, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 90 (2), 368–372.

Jey Aratnam, Ganga (2012): Hochqualifizierte mit Migrationshintergrund. Studie zu möglichen Diskriminierungen auf dem Schweizer Arbeitsmarkt. Basel: Edition Gesowip.

Kaplan, Edward L., and Paul Meier (1958): Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 53 (282), 457–481.

Lubotsky, Darren (2007): Chutes or Ladders? A Longitudinal Analysis of Immigrant Earnings, Journal of Political Economy, 115 (5), 820–867.

Steinhardt, Max Friedrich, Thomas Straubhaar, Jan Wedemeier, in collaboration with Sibille Duss (2010): Studie zur Einbürgerung und Integration in der Schweiz: Eine arbeitsmarktbezogene Analyse der schweizerischen Arbeitskräfteerhebung. Studie des HWWI im Auftrag von der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft vertreten durch das Bundesamt für Migration (BFM). Hamburg: Hamburgisches WeltWirtschaftsInstitut (HWWI).

About the authors

Sandro Favre (1985), lic. phil., research associate at the Department of Economics at the University of Zurich. Areas of work: labour market and migration.

Reto Föllmi (1975), Dr. oec. publ., Professor of Economics at the University of St. Gallen. Areas of work: macroeconomics, international trade, economic development, distribution of income and wage.

Josef Zweimüller (1959), Dr, Professor of Economics at the University of Zurich. Areas of work: empirical labour economics, inequality and growth, labour market and welfare state.